Limited Edition! This exclusive hardcover book is now available for purchase with free shipping to residents in the United States, Brazil, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Australia, and Japan. At present, we unfortunately do not yet have the means to ship directly to Africa. If you reside in any of the regions listed above, kindly place your order below and send your full name along with your shipping address to bantu.biblicalisraelites@gmail.com

WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE BANTU biblical and Enoch calendar

To Yisolele, a set-apart people… to the scattered Bantu, the Twelve Tribes of Tata Nzambi—our Sonini Nanini, Baba Mungu—whether in the Promised Land of Sub-Saharan Africa or dispersed abroad… to all who walk in His laws: understand this truth. The first four commandments instruct us to worship the Most High alone, and significantly, the fifth commandment calls us to rest in His holiness forever. This is why the Sabbath itself is not merely a rest day, but an act of worship. We know with certainty that the seed of the fallen watchers corrupted nearly everything they touched. The Scriptures testify that they whitewashed truth—misinterpreting sacred words, distorting history, and whitening the image of the biblical people (1 Maccabees 3:48). While the ancient Egyptians; though also Black—oppressed us at times, the serpent seed has always stood in opposition to the original man. Their goal has consistently been to erase and destroy all that belongs to the Most High.

- The different calendars

- The Gregorian Calendar Vs the Bantu Calendar:

Daniel 7:25 reveals how they altered times and seasons, and thus corrupted both the Sabbath and the calendar. First, they imposed the Julian solar calendar, and later, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar. This Gregorian system is nothing less than the calendar of the fallen watchers. In fact, the name Gregory itself is rooted in the Greek Grigori, meaning “fallen watchers.” Every day of the week and every month of their Greco-Roman year is dedicated to pagan deities, an open celebration of the beast system. From Moon-Day to Sun-Day, from January to December, their calendar is saturated with idolatry. For example, Friday is consecrated to Freya, a Norse goddess of death; Saturday to Saturnus, the god Saturn; and Sunday to the Sun-god. Through Christianity, Islam, and Judaism, these pagan observances were forced upon our people and the entire world as tools of mental and spiritual enslavement. Their calendar ensures that New Moons, Sabbaths, and the appointed festivals of the Most High fall upon their days of abomination, redirecting worship toward Satan (Isaiah 14:13–14; Revelation 13:8–9; Jubilees 6). Job 9:24 declares that the world has been handed into the power of the wicked. We witness this daily through the snares and manipulations of the alien seed, who scatter confusion at every step. Without diligent research, many assume March to be the beginning of the year simply because September derives from the Latin septem meaning seven. But this reasoning is no less misguided than the false worship of JC as a deity, though he never once proclaimed divinity himself. Indeed, Satan and his offspring are the true architects of confusion.

The Gregorian system was designed with purpose. Its roots lie in Rome, where Julius Caesar introduced the Julian calendar in 46 BC. It became the official calendar of the Roman Empire from 1 AD and was used across much of Europe. That calendar originally began in March and counted ten months. This explains why March, as the first month, aligned September with the seventh (7), October with the eighth (8), November with the ninth (9), and December with the tenth (10). Centuries later, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII altered it into the Gregorian calendar, which also influenced the structure of the modern Jewish calendar. Both January and March “New Years” are deliberate deceptions, crafted to mislead the masses even further. And what is truly absurd is that, after shifting to a twelve-month system, they still retained the original Latin names—names that no longer match their numbering—because they honored their pagan deities above all else. The word September, now positioned as the ninth month, originates from the Latin term Septem, meaning seven. October, placed as the tenth month, in truth signifies eight; November means nine, and December means ten. The reason these months were never properly realigned is that their original designations carry hidden significance within the Roman secret societies.

The Bantu calendar stands wholly distinct, neither rooted in the Jewish, Egyptian, nor Ethiopian systems, but existing as an independent order. It is founded not only upon the authority of scripture but also upon our ancestral Bantu customs, which themselves flow in harmony with the natural order. Just as the Romans anchored their calendar to their gods, so too the Egyptian calendar was bound to the deities of Egypt, entities we cannot acknowledge nor adopt. Yet Egypt remains an important marker in our restoration of the true Bantu calendar, for it was there that we sojourned longer than in any land outside our own. And it was in Egypt where the divine laws and commandments were last entrusted to Moshe. Scripture itself testifies that the children of Israel (Isolele) discerned the passage of time by the sun, while also marking their months by the cycles of the moon, from one new moon to the next, not as an act of worship but of observance. Remarkably, Bantu customs and languages alone preserve this ancient practice. In Kiswahili, as in many Bantu tongues, the same word Mwezi signifies month, moon, and the woman’s menstrual cycle. This linguistic truth resounds across Zulu, Kikuyu, Shona, Xhosa, Ndebele, Nyanja, Tswana, Kinyarwanda (Hutu), Bembe, Mashi, Havu, Nande, Lega, Fuluro, Bahunde, Nandi, Luyha, Luba, Kongo, and countless other Bantu languages. Even the Kiswahili word for the full moon, Mbalamwezi, bears witness to our ancestors’ profound understanding of the lunar cycle.

This enduring continuity is not mere coincidence, it is one of many living proofs that the so called Bantu peoples are in truth the Twelve Tribes of the biblical Israelites, scattered to the four corners of the earth. Beyond this, numerous other correspondences affirm our identity: circumcision as an ancient Bantu rite, our people’s distinction as the only truly monotheistic nation, our traditions as the living Torah, and our languages as the original tongue of the Habiru (Hebrews). Yet today, amid the confusion sown by deception, some measure time by the sun alone, others by the moon alone, still others by the stars, while many more are compelled to submit to the Judeo Greco Roman calendar of white dominion. All of these paths lead astray. Our ancestors, however, left us a clear witness in our languages and culture, pointing to the true order of time. This great derailing confusion was long ago foreseen and prophesied by Bantu prophets from the very beginning.

2. The Ethiopian Calendar?

Bantu people (original Israelites) should not follow the Ethiopian calendar, nor the Egyptian calendar. Some claim that the Ethiopian New Year represents the original New Year; this is not accurate. If we examine Genesis 1:14, it becomes clear that the true calendar is based on three lights—the sun, the moon, and the stars—not a single star. The verse reads: “And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years.” This establishes the foundation of the original calendar, showing that a calendar based solely on one star is incomplete.

Some may argue that Exodus 12:2, which states, “This month shall be unto you the beginning of months: it shall be the first month of the year to you,” suggests a different New Year specifically for the Israelites. However, the Book of Enoch, written thousands of years earlier, confirms in Enoch 72:5 that both Noka and Nowa were instructed to follow the same calendar later given to Moshe during Exodus. This demonstrates that the biblical calendar is a continuation of an original system, not a separate creation. It is important to understand the spiritual symbolism in the instructions given in Exodus 12. For example, the preparation of Pasaka and the application of blood on the doorposts was specific to that event and carries deep spiritual meaning, rather than a permanent dietary restriction. In Abantu culture, domestic animals such as cows, lambs, and goats have been used for food and for ceremonial purposes, such as the bride price, for thousands of years.

Different African tribes developed calendars based on their local environments and cultural factors. For the Abantu, months have always followed lunar cycles, while years, seasons, and other temporal measures are governed by the sun, moon, and stars. Indeed, the words for “moon” and “month” are consistent across Bantu languages, reflecting this shared understanding. The Ethiopian calendar, in contrast, is based on Sirius, and its 13-month structure—twelve months of thirty days plus a thirteenth month of six days—does not align with the lunar cycle or the solar year. It does not observe a New Moon Feast each month, does not recognize the weekly Sabbath, is seven years behind the Gregorian calendar, and the six-day thirteenth month offers no designated day of rest. Understanding these distinctions allows us to see that the original calendar is rooted in the careful observation of the sun, moon, and stars, and is deeply aligned with both natural cycles and spiritual order.

3. The Bantu land as evidence of the biblical calendar

As we deepen our engagement with these revelatory discoveries, it is of utmost importance to remind everyone that the Promised Land is not in the Middle East, but in Sub-Saharan Africa. This has already been established and supported with substantial evidence. For those seeking a rapid understanding, I encourage reviewing other articles on the subject. Based on this knowledge of the true location of the Promised Land, we will anchor our study here. We will consider all factors, including the climatic conditions of Sub-Saharan Africa and extending to ancient Egypt, as these are indeed the biblical locations—not the so-called Middle East. It was at Mount Sinai that our Bantu ancestors received these divine instructions from the Most High, to be observed eternally. If the Promised Land is not the tiny, arid, and colonially appropriated territory in the Middle East, then clearly the true Mount Sinai cannot be located there either. The Israelites did not journey to the Middle East from Egypt; scriptures affirm that they went “up” from Egypt. Geographically, Sub-Saharan Africa—the land of milk and honey—occupies a significantly higher altitude than both Egypt and the Middle East.

Exodus 12:1–11, 13 states that the day Moshe received these instructions was the first Passover, celebrated at the full moon at Mount Sinai, two months’ travel from Egypt. This places the event well beyond the borders of Egypt, yet still within the deserted regions of the Sahara. Egypt, despite its northern location closer to Europe, experiences seasons remarkably similar to those of much of Sub-Saharan Africa: dry and rainy, though its rains are shorter in duration. Even under Greek and Roman dominion, Egypt (formerly Kemet) consistently observed its New Year in the Gregorian month of September, either due to collaboration with Kush or because September, like in Sub-Saharan Africa, is the optimal month for sowing crops. This aligns perfectly with the biblical term “Abib,” meaning “to sow seed,” with the former explanation likely being the truer.

NOWA was born in Shulon-ga, east of Eden, the very region where his great-grandfather Enoka first received the original calendar instructions from the Most High. Eden (also known as Alkebulan) was geographically situated around the Great Lakes region, while “east of Eden” corresponds to Central Eastern Africa, encompassing the old land of Kush, which later became Babylon/Mesopotamia. The timelines of this area align with Egypt, and Ethiopia in this region observes the same first month of the year, September, according to the original calendar. According to colonial scholarship, these regions recognize only two main seasons, even at the southernmost reaches: the dry and the rainy. For example, in Eastern Congo, in the town of Goma, the dry season spans June to August, with temperatures ranging from 12.8°C (55°F) to 19.9°C (67.8°F), lasting less than three months. The rainy season runs from September to May, with temperatures between 13.9°C (57°F) and 21°C (69.8°F), dominated by heavy monsoon rains. The equator cuts through the Great Lakes region, providing exceptionally favorable conditions for habitation, farming, and agriculture.

In most of Sub-Saharan Africa, August is considered the optimal month for sowing seeds, as September brings heavier rains, promoting germination and new beginnings (Kiola, the first month). The soil in these regions is regarded as among the most fertile on the planet, perfectly aligning with the Book of Jubilees, which describes the Promised Land (all of Sub-Saharan Africa) as a land of everlasting abundance, neither hot nor cold, given to Shem for inheritance. Furthermore, the astronomical seasons of Southern Africa correspond as follows: September to November marks Spring, December to March marks Summer, March to June marks Autumn, and June to August marks Winter. This seasonal cycle is consistent across all Southern African countries.

4. Bantu languages as evidence of the original Calendar

The Bantu word Mwezi, along with its variants across different Bantu dialects—such as mwesi, mwetsi, mweri, mweji, mweni, mwedzi, umwezi—applies to the moon, the month, and the menstrual cycle. This term is not merely a linguistic artifact; it represents an original concept of the Abantu calendar. Remarkably, this same word was later adopted by the Romans, the Portuguese, and the Arabs. Some may argue that the Bantu term Mwezi, appearing in every Bantu language, was borrowed from the Roman Latin mensis (month), and that the Romans indeed had contact with the Bantu. While it is true that the Romans engaged significantly with the Bantu long before the 1400s and that their African campaigns, beginning with the invasion of 146 BCE, reached the far corners of the continent, it would be disingenuous to claim that the Bantu “copied” the word from the Romans. Such an assertion feeds colonial narratives while omitting the fact that the Romans were primarily the ones taking and exploiting African knowledge and culture.

From the Roman perspective, appropriation was instinctive—they seized everything they could: from the Kemetic concepts of Christianity and the trinity, to Bantu practices such as circumcision, monotheism, and the calendar itself. Their systematic plundering intensified, and it was not until the 1400s AD, after the Moors had been expelled from Europe—a civilization that had ruled and educated the continent for over 800 years—that European powers returned, seeking not only conquest but also the rewriting of history. A careful investigation into the European Renaissance will confirm this pattern of appropriation. Indeed, the Romans and Greeks were present in Africa long before the 1400s, but they lacked the educational and cultural foundation to influence Bantu literature. Instead, the reverse occurred: in 146 BCE, they stole knowledge wherever possible. However, it was through the Moors, arriving around 700 AD—descendants of various African tribes and ethnicities, occupying positions of power from kings and queens to popes, educators, and heroes—that the stolen knowledge was translated and reinterpreted. These Moors were not ordinary people; they were leaders, scholars, and custodians of advanced civilization.

When one examines Christianity closely, inconsistencies emerge because it was, in essence, a patchwork of stolen and repurposed African, Egyptian, and regional knowledge. This explains why Jesus is described alternately as the Son of God, God Himself, and a descendant of Adam; why one God is represented as three; and why Egyptian sun worship is demonized while Sunday—the day of their sun/son god—is venerated, often marked with a cross derived from the Egyptian Ankh. The Romans cared little for doctrinal consistency; their priority was the sense of power and identity they derived from these appropriations. The Abantu predate the Romans, the Jews, and the Arabs. Christianity emerged in 325 AD, Islam in 610 AD, and Judaism as known today in 1858 within the Russian Empire. Prior to these faiths, there were the Abantu—some of whom were recognized as Yisolele, the “set-apart people.” The Bantu calendar was never borrowed from the Egyptians, Babylonians, or any other civilization; it is an indigenous, eternal custom, preserved among us since the dawn of time.

5. The book of Enoch as evidence

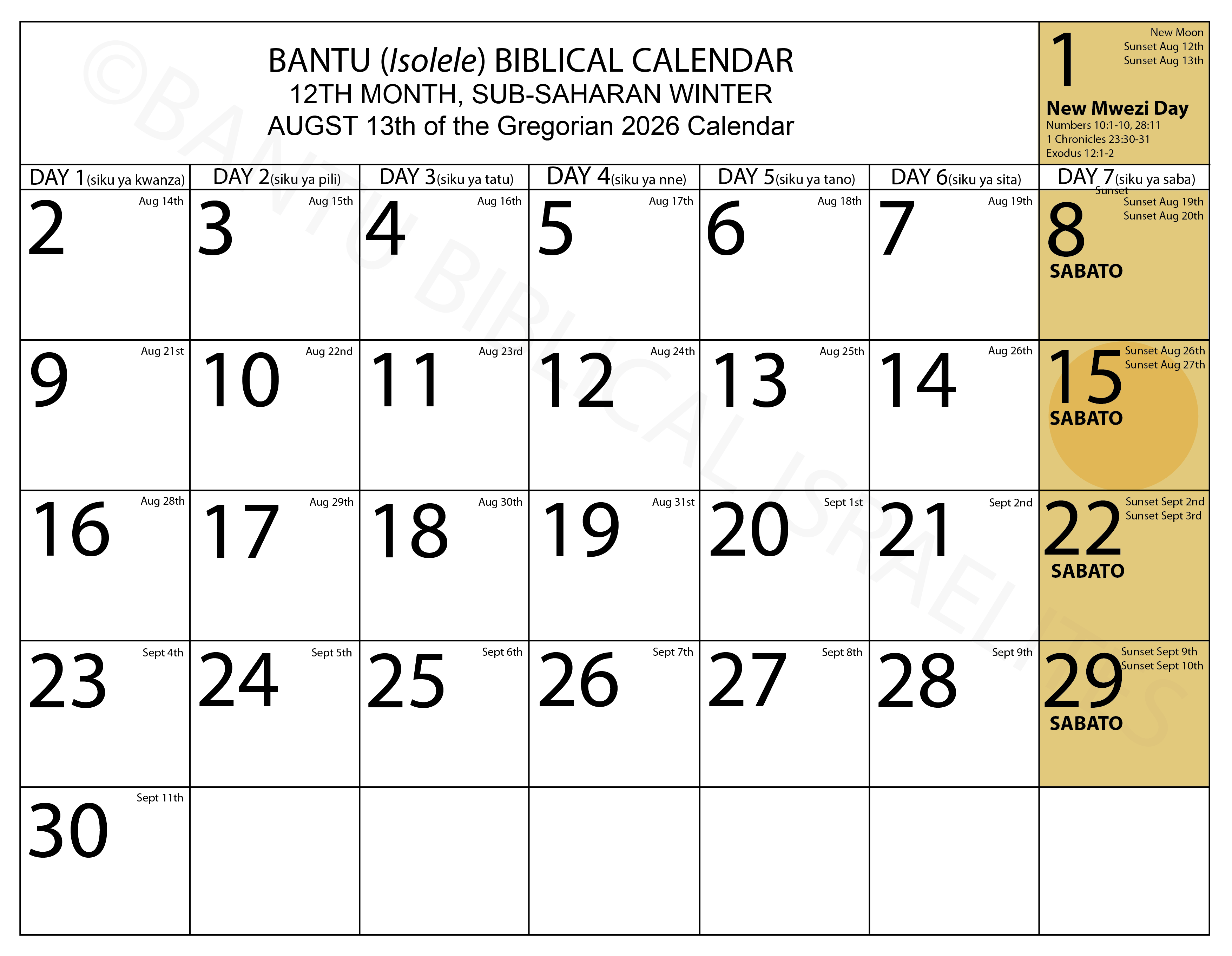

In our Bantu traditions, we observe both the sun and the moon. Our Bantu year typically comprises twelve months, with each month spanning between 29 and 30 days, beginning with the new moon, which usually occurs around September. While spring in the Northern Hemisphere begins in March, in the Southern Hemisphere it commences in September. This accounts for the seasonal differences between the two hemispheres; for example, when it is winter in Europe and North America, it is summer in Sub-Saharan Africa and Australia, and when it is autumn in Europe and North America, it is spring in Sub-Saharan Africa. It is essential to understand that although the moon completes its orbit around the earth in 27.3 days, the complete lunar phase cycle—from one new moon to the next—takes 29.52 days. Scripture supports the observance of both the sun and the moon. Revelation 11:1-3 and the Book of Enoch 74:9-17 emphasize this necessity. Enoch 74:9-17 states:

“9. Thus I saw their positions; how the Moon rose and the Sun set in those days. 10. And if five years are added together, the Sun has an excess of thirty days. For each year, of the five years, there are three hundred and sixty-four days. 11. And the excess, of the Sun and the stars, comes to six days. In five years, with six days each, they have an excess of thirty days, and the Moon falls behind the Sun and the stars by thirty days. 12. And the Moon conducts the years exactly, all of them according to their eternal positions; they are neither early nor late, even by one day, but change the year in exactly 364 days. 13. In three years, there are 1,092 days, and in five years 1,820 days, so that in eight years there are 2,912 days. 14. For the Moon alone, the days in three years come to 1,062 days, and in five years it is fifty days behind. 15. And there are 1,770 days in five years so that for the Moon the days in eight years amount to 2,832 days. 16. For the difference in eight years is eighty days, and all the days that the Moon is behind, in eight years, are eighty days. 17. And the year is completed exactly, in accordance with their positions, and the positions of the Sun, in that they rise from the Gates from which the Sun rises and sets for thirty days.”

Let us break this down for clarity. The lunar month lasts approximately 29.5 days. To simplify calculations, we disregard the half days, as half a day cannot be counted on a calendar. Twelve half-days over the lunar cycle equal six full days. This gives us six months of 30 days and six months of 29 days, totaling 354 days per lunar year. This method aligns the lunar months with the annual lunar cycle. However, a 354-day lunar year falls ten days behind the solar year. Enoch explains that multiplying 354 days by three years results in 1,062 days. Since the solar year comprises 364 days, the moon will lag behind the sun by 30 days over three years, meaning those who follow a purely lunar calendar will be consistently behind by a month every three years. To reconcile the cycles of the sun, stars, and moon, Enoch prescribes adding a 13th month of 30 days every third year. This adjustment ensures that the sun, stars, and moon align precisely in the Southern Hemisphere’s September spring and preserves the correct timing of Sabbaths, new moon festivals, and other appointed festivals as prescribed in Scripture. This method transforms the lunar calendar into a lunisolar calendar.

By adding the 30-day month, the lunar cycle over three years becomes 1,092 days. Dividing this by three yields 364 days, which corresponds to the solar year. In this manner, the sun, moon, and stars are harmonized, faithfully maintaining their appointed positions in accordance with divine order. Importantly, the Book of Enoch warns against those who reject the leap month, attempting to maintain a strict 364-day year. Such disregard leads to errors in observing Sabbaths, new moons, and festivals. Enoch states: “For after thy death, thy children will corrupt, so that they make a year only 364 days, and on this account, they will err concerning the new moons and the Sabbaths and the fixed times and the festivals and will ever eat blood with all kinds of flesh.” This serves as a solemn reminder that the lunisolar calendar, incorporating both sun and moon, is essential for maintaining alignment with the Creator’s ordained times.

6. Bantu languages against the Sunrise Sabbath theory:

Regarding those who suggest that the Sabbath should be observed from sunrise to sunrise because we are children of light and not of darkness, let me clarify my perspective. First, I do not believe that anything Tata Nzambi created is inherently evil. Darkness itself is a blessing; it provides us an opportunity to rest, just as He concluded His work each day and awaited the next to continue. The night allows us to rest, reenergize, and purify ourselves so that we may begin anew in the morning, refreshed. As Proverbs 3:24 reminds us, “When you lie down, you will not be afraid; when you lie down, your sleep will be sweet.”

I will be honest: I once agreed with the sunrise-to-sunrise Sabbath. Yet, as I began to study the scriptures closely, independent of human interpretation, I began to discern the patterns of how the Most High truly desires His days to be observed. From the very beginning, before light existed, there was darkness. Genesis 1:2-3 records: “And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. And God said, Let there be light: and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.” It is evident from scripture that the Sabbath is observed from sunset to sunset. This timing allows preparation for the sacred day during the morning. Genesis 1:5, when approached with an open heart and led by the Spirit of the Most High, makes this clear: “And God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.” The conclusion of each day is marked by sunset, signaling the transition to the next day.

In many Bantu traditions, the sun dictates the rhythm of life. Our grandparents understood time by observing the shadows cast by the sun. The Bahunde people of the DRC divide the day into two segments: daylight from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., and night from 6 p.m. to 6 a.m. Interestingly, their word for night, kiro, also signifies a full 24-hour day, confirming that their day begins at sunset. Similarly, in Shona, the word zuva denotes both “sun” and “day,” reflecting the sun’s central role in measuring time. In Kikongo, Lingala, and Kiswahili, a week consists of seven days. In Kikongo, the seventh day, Samba, signifies rest, praise, and prayer. In Kiswahili, saba represents seven, giving rise to siku ya saba, the day of God (siku ya Mungu). Colonial influence, however, converted this sacred day into the Gregorian Sunday, which misaligns with the lunisolar rhythm of the Bantu calendar. The term evolved from Samba to Sabato and ultimately to modern Shabbat or Sabbath. Among the Bahunde, the word iyinga for the seventh day also denotes the end and beginning of a week.

Leviticus 23:32 reinforces this sunset-to-sunset understanding: “It is a day of sabbath rest for you, and you must deny yourselves. From the evening of the ninth day of the month until the following evening you are to observe your sabbath.” Notably, no scripture endorses a sunrise-to-sunrise Sabbath; such notions remain speculative. Nehemiah 13:19 affirms the same principle: “And it came to pass, that when the gates of Jerusalem began to be dark before the Sabbath, I commanded that the gates should be shut, and charged that they should not be opened till after the Sabbath: and some of my servants set I at the gates, that there should no burden be brought in on the Sabbath day.” Sunset-to-sunset observance still includes the daytime portion of the Sabbath, beginning in the morning. Scriptures such as John 11:9; John 9:2; Genesis 2:1-3; Exodus 20:8-11; Isaiah 58:13-14; Isaiah 56:1-8; Acts 17:2; Acts 18:4, 11; Luke 4:16; Mark 2:27-28; Matthew 12:10-12; Hebrews 4:1-11; Genesis 1:5, 13-14; and Nehemiah 13:19 all confirm this. The true Samba (Sabbath) does not align with any modern calendar and is neither Saturday nor Sunday.

7. Evidences to dismantle the Full Moon as New Moon Theories

Regarding the claim that a month should commence with the full moon, this contradicts Bantu cosmology. The term “new” signifies beginnings—from emptiness to fullness. To assert that a month begins at the full moon is akin to claiming that life begins at death. Life begins at birth, and any ideology opposing this principle is fundamentally unnatural.

Sub-Saharan African communities have long revered the full moon, gathering for song, dance, and storytelling. Yet this observance is a mid-month celebration, not the commencement of a month. Psalm 81:3 captures this insight: “Blow the trumpet at the new moon, at the full moon, on our feast day.” Even Passover occurs on a full moon, following the natural lunar cycle rather than the imposed Gregorian calendar. The months adhere to both lunar and solar cycles, not arbitrary seasonal markers. Even if spring in Sub-Saharan Africa begins on September 21, the first month may commence before or after, depending entirely on the lunar cycle.

Those who claim our calendar is borrowed from the Jewish system overlook history: Jews, as a modern nation-state, have existed only since 1948, whereas Bantu peoples have inhabited these lands since creation. The Jewish new year, observed in the northern hemisphere, aligns with September in the southern hemisphere, while their Passover festival remains fixed in March or April, coinciding with Easter/Ishtar. This underscores that the original calendar and its festivals are deeply rooted in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Furthermore, Jewish Sabbath observance relies on the Gregorian calendar (Saturday), highlighting three entirely distinct calendrical systems. If the devil is the author of confusion, then Judaism, in its current form, has become a vehicle for his deception.

8. False solar only Calendars

There is a group of individuals teaching that both years and months should be based solely on the solar system. They operate under the name “Bantu Re-Education TV.” Their central argument is that the moon arrives ten days earlier than expected, and therefore cannot be trusted as a timekeeper. They base these claims on a text known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, allegedly discovered in the modern state of Israel. According to them, this text contains a breakdown of months with 30 and 31 days, aligning—presumably—with the Gregorian calendar. It is said to have been discovered in 1947, though it was allegedly written in the first century. However, crucial details remain uncertain: the authorship is unknown, and it is suspicious that its discovery coincides with the year the impostors occupied Palestine. Moreover, the use of Gregorian dates and names such as Sunday and Monday strongly suggests that the text has been tampered with. The Gregorian calendar was not invented until 1582, which raises serious doubts about the authenticity of the scrolls’ dating. While the scrolls may contain some useful information, the overarching evidence points to significant Roman influence. Anyone can verify this by comparing the Gregorian calendar with the Dead Sea Scrolls’ calendar—the scrolls effectively dictate which Gregorian dates their Sabbaths should fall on.

Even more telling is the correlation between the Dead Sea Scrolls’ calendar and the oldest known Roman calendar, the Romulus calendar, which also ignores new moon days. These factors alone cast serious doubt on the scrolls’ credibility and suggest a Roman hand in their construction. The scrolls are inconsistent and incomplete; for instance, they recognize only a few months. The first month is omitted entirely, counting begins from the second month, and after the sixth month, it jumps straight to the twelfth month. Notably, the scrolls themselves refer to this as a “sectarian calendar,” deriving from the root word “sect,” indicating its limited and biased perspective. Before accepting anything merely because it appears ancient, we must weigh it against our Bantu culture, other historical documents, and the Bible. If there is no support from our language, culture, or scripture, we can conclude that the material is either foreign or tampered with, particularly when it is rife with inconsistencies. Interestingly, those who follow this calendar often ignore every biblical and apocryphal verse affirming the new moon as the start of the month. Because the Bible directly contradicts their claims, they turn to the Book of Jubilees and the Book of Enoch for support. They assert that Jubilees 6:36-37 condemns those who follow a lunisolar calendar and claim that Enoch presents a solar-only calendar.

Yet, the very reasoning they use to reject lunar months applies equally to a solar-only calendar. They argue that Enoch 73 emphasizes a solar calendar, but a close reading from Enoch 71 through 74 demonstrates the opposite: Enoch 73 actually supports lunar months within a lunisolar framework. Enoch 71 highlights the importance of the sun, while Enoch 72 emphasizes the moon. Crucially, Enoch 72 specifies the proper start of the month: verse 5 states, “At the time it appears, and becomes to you the beginning of the month. Thirty days it is with the sun in the gate from which the sun goes forth.” Here, the text clearly affirms that the new moon marks the beginning of the month. Chapter 73 then provides a detailed breakdown of both lunar and solar cycles. It acknowledges that the lunar year is ten days shorter than the solar year but gives explicit instructions to reconcile the two. Every third lunar year, thirty days must be added to the moon to ensure that the lunar months align with the sun, guaranteeing that new moons, Sabbaths, and appointed feasts are observed correctly. Essentially, Enoch instructs that the moon governs the months, while the sun ensures alignment over time, reconciling the cycles every three years to maintain consistency. Anyone approaching this objectively can clearly see the lunisolar principle at work.

When reading Sirach 43:1-10, we encounter a clear and profound explanation of the significance of the new moon. From verse 6, it states: “He made the moon also to serve in her season for a declaration of times, and a sign of the world. From the moon is the sign of feasts, a light that decreases in her perfection. The month is called after her name, increasing wonderfully in her changing, being an instrument of the armies above, shining in the firmament of heaven.” This passage, repeated in Ecclesiasticus 43:6-8, unmistakably establishes that the months are determined by lunar cycles.

Turning to the Book of Jubilees, which some erroneously claim rejects lunar months, we find in chapter 6, during the first half, a detailed account of how Enoch honored the new moons to guide him through the flood. By verse 19, we learn that Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob followed the same calendar observance as Enoch. Verses 23–30 reiterate the importance of celebrating new moon festivals, while verse 32 emphasizes the necessity of keeping a year of 364 days. Verse 33 issues a solemn warning: neglecting these observances will disrupt the natural order, causing the seasons and years to fall out of alignment, leading to the disregard of sacred ordinances. Verse 34 underscores this further: “And all the children of Israel will forget and will not find the path of the years, and will forget the new moons, and seasons, and sabbaths, and they will go wrong as to all the order of the years.”

Critics often point to verse 36 as contradictory: “For there will be those who will assuredly make observations of the moon—how it disturbs the seasons and comes in from year to year ten days too soon.” Here, many solar-only calendar adherents fail to distinguish between “observe” and “make observations,” two terms with distinctly different meanings. To observe is to faithfully keep or follow, whereas to make observations means to study carefully or judge based on scrutiny. Verse 36 clearly refers to the latter: many will merely study the moon, seeing how it disrupts the seasons by advancing ten days each year, and as a result, reject the original lunar calendar in favor of pagan systems. These systems intentionally distort the natural order, turning sacred days into profane observances, confounding the holy with the unclean, and misaligning months, sabbaths, feasts, and jubilees.

The Book of Enoch, chapters 72 and 73, along with hundreds of other biblical passages, affirm the new moon as the marker of a new month. Notably, in every Bantu dialect, the words for “moon” and “month” are identical, corroborating the practices described in the Book of Enoch, the Book of Jubilees, and throughout the 66 books of the Bible. Furthermore, the oldest known mathematical and astronomical artifact, discovered in Ishango in East Africa (east of the DRC), demonstrates that the Bantu peoples were already employing a lunar calendar thousands of years ago. This evidences that solar-only interpretations are fundamentally flawed, and their attempts to twist these verses to justify a false calendar system are misguided. For those who comprehend English accurately and whose minds remain untainted by man-made distortions, this truth is straightforward and undeniable.

Certain individuals wrongfully invoke Jubilees 2:9 as evidence for their sun-only calendar, but they tear the verse out of its proper context. Here is what Jubilees 2:9 actually declares: “And God appointed the sun to be a great sign on the earth for days and for sabbaths and for months and for feasts and for years and for sabbaths of years and for jubilees and for all seasons of the years.” Nowhere does this passage claim that months are governed exclusively by the sun. Rather, it explicitly states that “He appointed the sun to be a great sign on the earth.” This sign applies to months, days, Sabbaths, and years.

First, let us consider the meaning of a “sign.” Etymologically, a sign is a mark, an indicator, something observable. The sun is indeed such a sign for all matters of time, because everything in the biblical reckoning begins at sundown: the month begins at sundown, the Sabbath begins at sundown, the festivals begin at sundown, and even the year begins at sundown—the observation of the sun’s setting. That is the purpose of a sign: to indicate when a transition occurs. The sun thus governs the rhythm of time itself—this is undeniable. Yet there is one vital distinction: while the month begins at sundown, it begins specifically at the sundown of the new moon. Why? Because a sign must be something you can look to for instruction. One cannot simply gaze at the sun and determine the exact day of the month. That role belongs to the moon. The moon serves as a clearer witness of the passage of months, marking their beginning and their end—a practice our ancestors have observed faithfully for centuries. In short, the sun determines the time of day when the month begins, but the moon determines which day it is. The same principle applies to Sabbaths, years, and appointed feasts. They function in harmony: the sun governs time, while the moon governs count and order.

Now, if we examine Jubilees 2:9 closely, we notice two striking possibilities. Either verse 8 introduces the sun as a sign for days, Sabbaths, months, and years in unity with the other lights, which aligns with everything we have established—or, more likely, the translator omitted the words “and moon and stars” in verse 9. Why? Because the flow of thought becomes inconsistent. In verse 8, the text affirms that on the fourth day the Most High created the sun, moon, and stars to govern the days and nights. Yet in verse 9 the focus suddenly narrows to the sun alone, before verse 10 shifts back to all three lights. This strongly suggests that verse 9 originally included mention of the moon and stars as well. For confirmation, we turn to Genesis 1:14–15, which provides a clearer witness: “Then God said, ‘Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and for years; and let them be for lights in the expanse of the heavens to give light on the earth’; and it was so.”

Notice carefully: Genesis affirms that it is the combined role of the sun, moon, and stars to serve as signs for seasons, days, and years. This perfectly aligns with what we have explained. Each luminary plays its unique role in regulating the days, Sabbaths, months, and years. To deny this harmony is either to harbor ulterior motives or to succumb to intellectual laziness. The truth is clear—not only in the Scriptures and the Apocrypha but also in the living testimony of Bantu culture. As for the matter of leap years, the concern is less about the year itself and more about identifying the beginning of each month. This is because Sabbaths are measured by months, not by years—counted from the first Sabbath to the fourth, month after month. If the reckoning of months is wrong, then everything else will be thrown into error. Scripture never records the celebration of a New Year in the way many imagine today. What it does emphasize repeatedly are the feasts of the new moon. This does not mean that the New Year is unimportant, but it was never a central celebration. What was consistently celebrated at the turning of time was the Mwezi—the moon, the marker of the month.

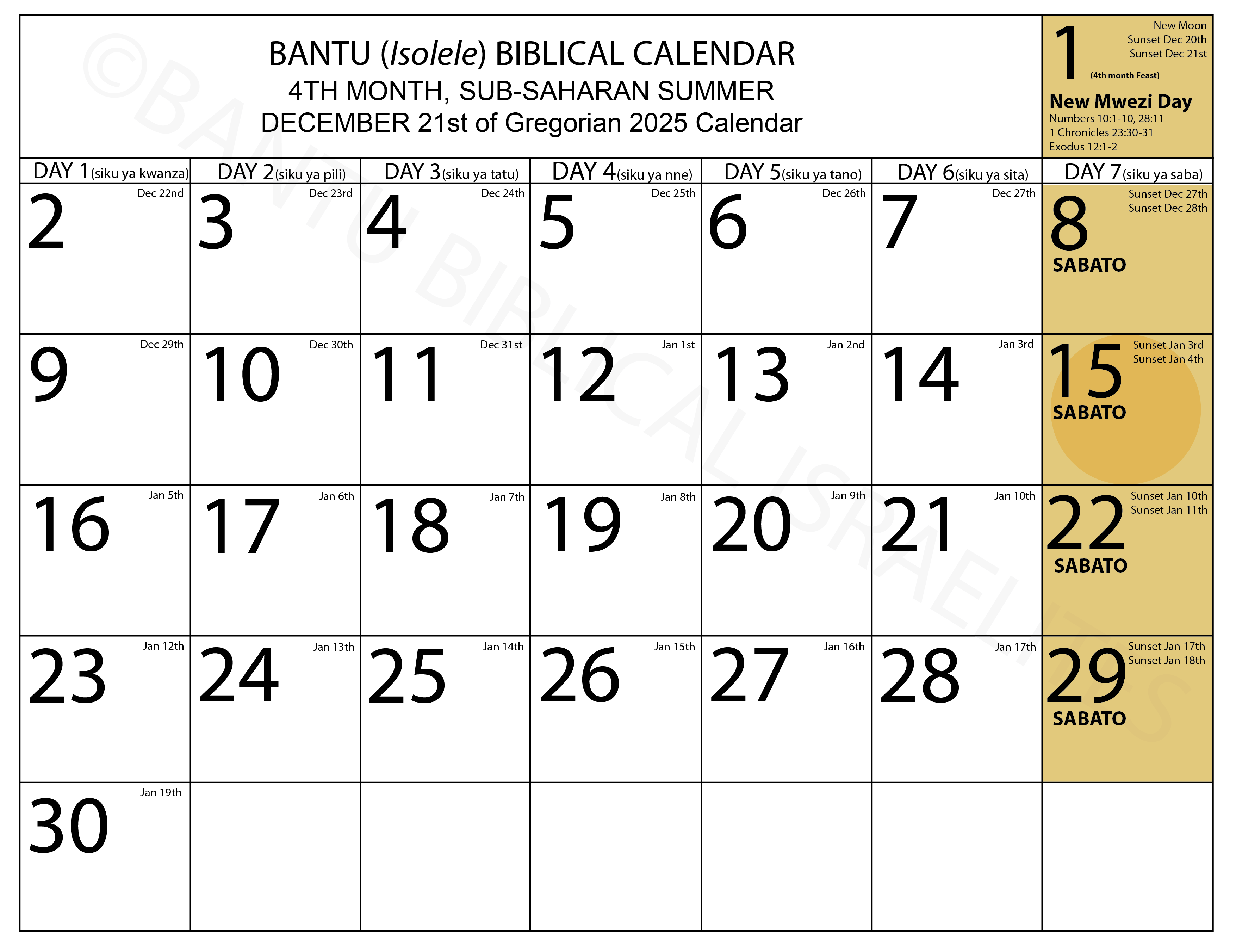

Last but not least, we know that the new moon is a consecrated day, a day upon which no work is to be done. According to Ezekiel 46:1, the gate of the inner court of heaven that faces the East is opened only on the day of the new moon and on the Sabbath; on every other day, it remains shut. If this is the divine order, then when Exodus 20:9–11 and Exodus 34:21 declare, “Six days you shall labor, but on the seventh day you shall rest,” it becomes evident that first the new moon feast is to be observed, followed by six days of labor, and then the Sabbath. This order places the first Sabbath of every month on the eighth day. This same pattern is reflected in Joshua 6, when Joshua and the children of Israel fought on the seventh day. That “seventh day” was clearly not the Sabbath, but the day immediately preceding it. Moreover, the Book of Jubilees and the Book of Enoch affirm that the new moon was kept as a sacred day even in the time of Noah.

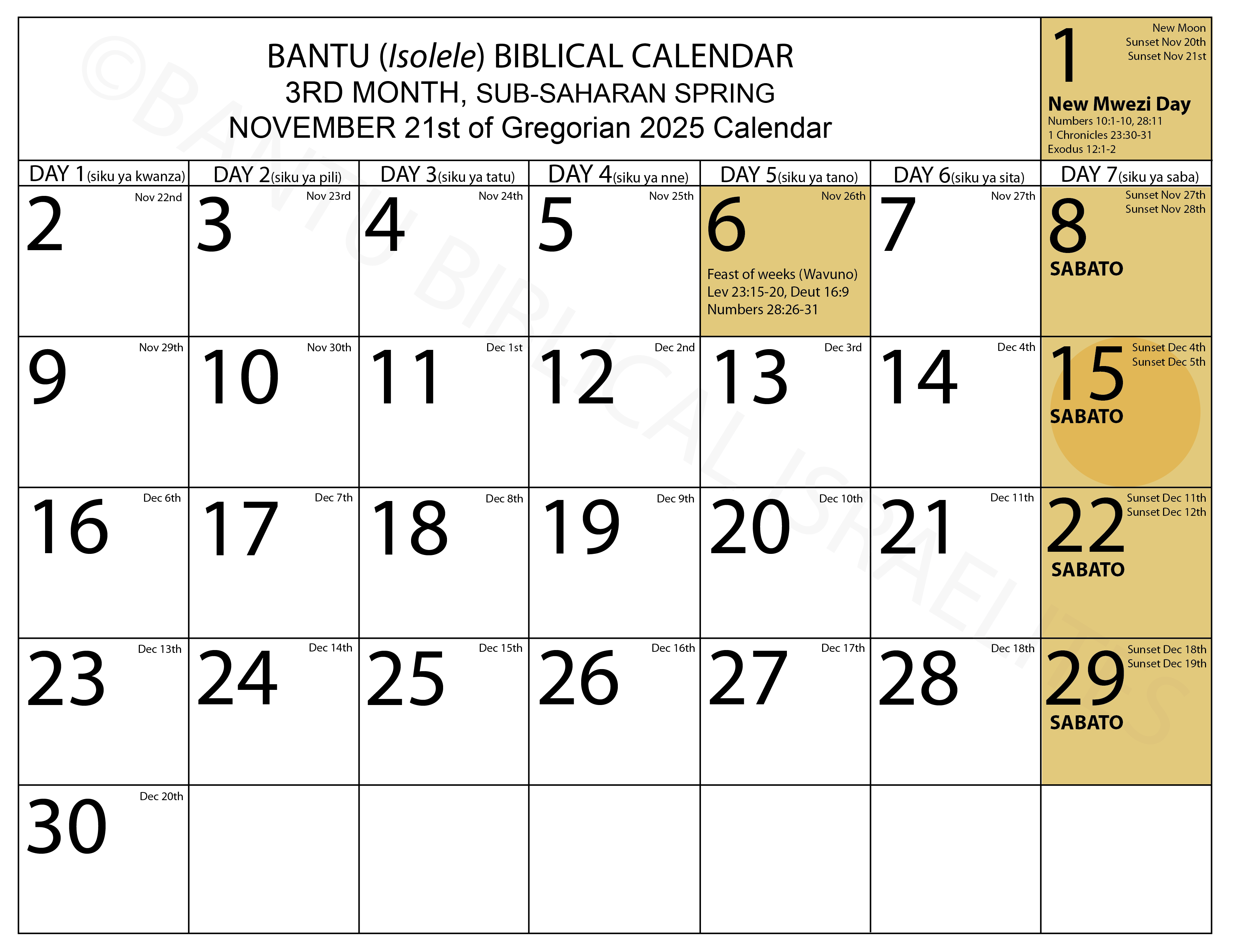

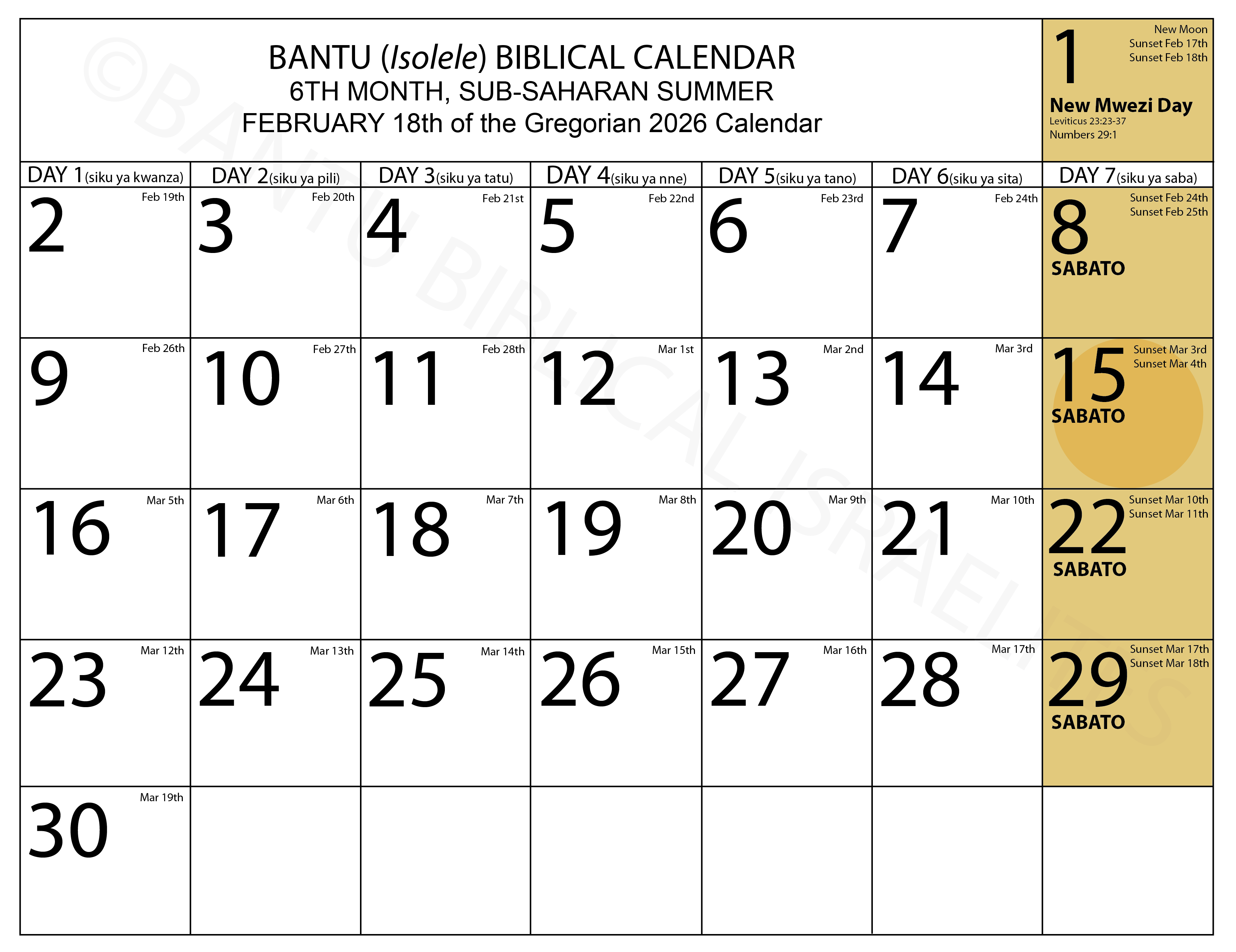

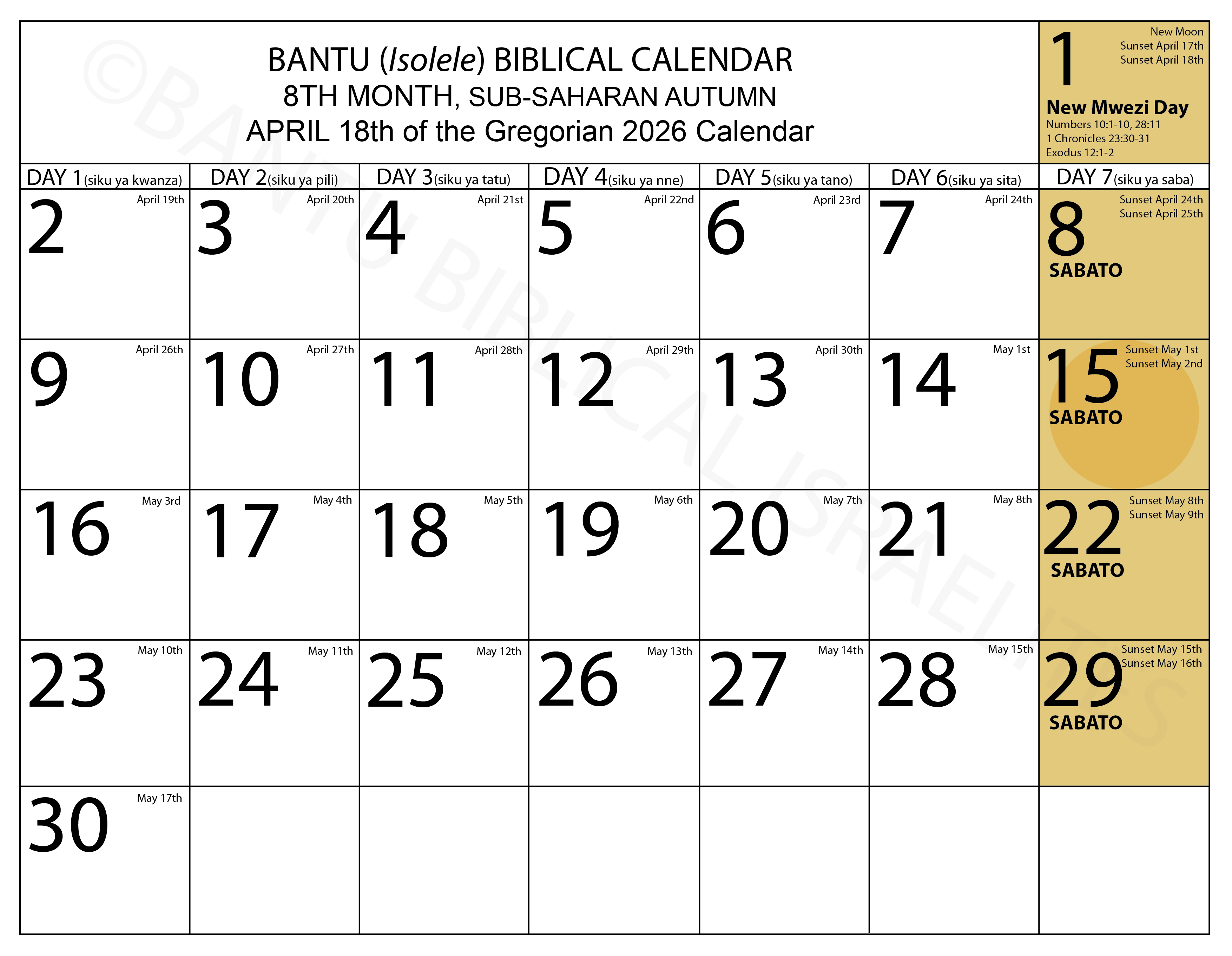

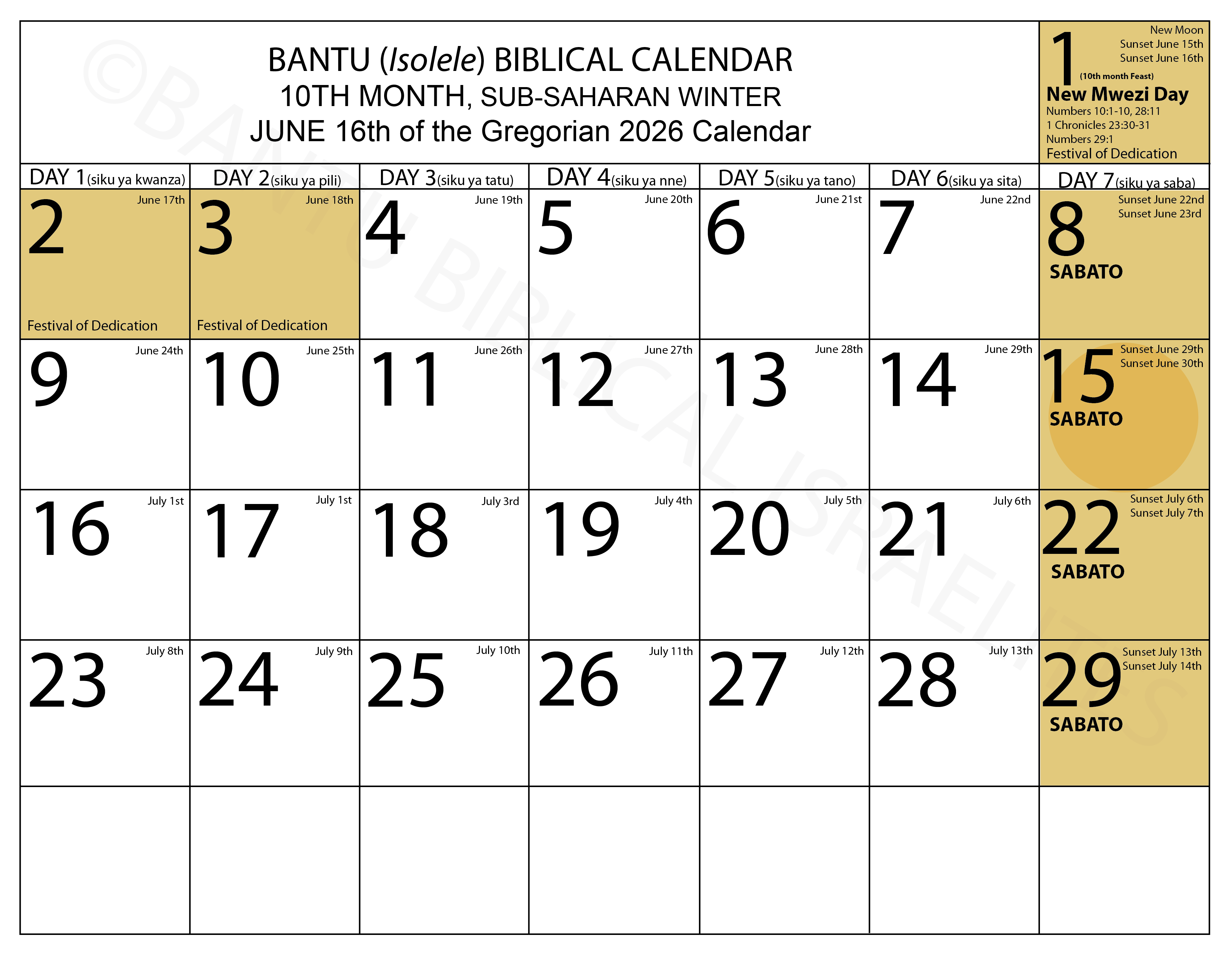

Beyond the new moon feasts and Sabbaths, which have already been established, there are other appointed Festivals that must be observed every year. These are recorded in Jubilees 6:23, showing how our patriarch Noah observed them, and in Exodus 12 and 13, which testify to the observance of Moshe and our Bantu ancestors. These feasts are ordained for eternity: Passover is to be celebrated on the 14th day of the first lunar month (Exodus 12; 2 Chronicles 35:1–19). The Festival of Unleavened Bread begins on the 15th day of the same first month and continues for seven days (Exodus 12:8–20). The Festival of First Fruits falls on the same 15th day of the first month, celebrated together with the Feast of Unleavened Bread (Leviticus 23:9–14). The Festival of Weeks (Pentecost) is observed on the 4th day of the third lunar month, precisely 50 days—or seven full weeks—after Passover (Leviticus 23:15–20; Deuteronomy 16:9; Numbers 28:26–31). The Festival of Trumpets is proclaimed on the 1st day of the 7th lunar month (Leviticus 23:23–37; Numbers 29:1). The Day of Atonement is kept on the 10th day of the 7th lunar month (Leviticus 16; Leviticus 23:26–32; Numbers 29:7–11). The Festival of Booths (Tabernacles) begins on the 15th day of the 7th lunar month, five days after Atonement (Leviticus 23:33–43; Deuteronomy 16:13–15; Numbers 29:12–40). Finally, the Feast of Dedication is celebrated on the 25th day of the 9th lunar month (1 Maccabees 4:52–59; John 10:22–23).

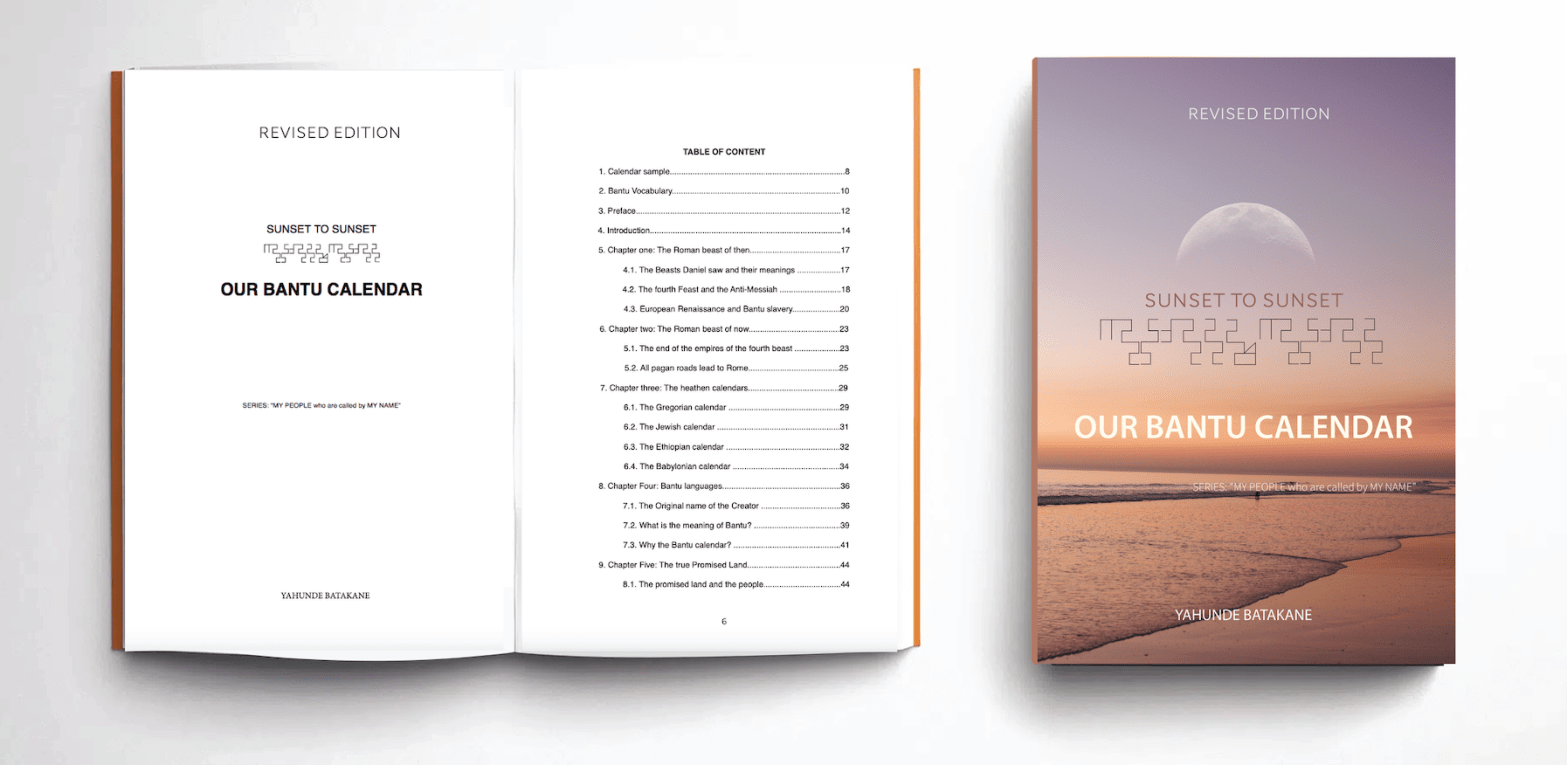

It is my hope that this calendar will serve as a guide for us all, enabling us to observe the Sabbath as it is commanded in the Scriptures, and to faithfully keep the biblical festivals ordained by the Most High, rather than the pagan feasts into which we were misled—feasts that directly oppose the divine order of creation. Through the Spirit of the Most High, I have labored for years—observing both the lunar and solar cycles, revisiting geography and history, exploring our ancestral languages, and studying Bantu customs. This has required prayer, sacrifice of time and energy, private debates within the awakening community, and the continual revisiting of the Scriptures. Out of this long and careful process, guided by wisdom from above, something concrete has emerged. Yet, despite the effort invested, I encourage each of you to pursue your own study, carefully examining the biblical references and historical sources provided. If you have questions, please do not hesitate to reach out, for this is still a work in progress and we do not claim to have all the answers. If you would like to begin with this foundation and need a free PDF copy, feel free to inbox us.

2. The Five Major Feasts:

1. The Passover (Pasaka):

The very term Pasaka derives from the Bantu tongue, and Scripture traces its origin back to the Exodus. According to Exodus 12, on the evening of the 14th day of the first month of the Bantu year (Spring), families gathered in their households to sacrifice a yearling sheep or goat.

The first observance of Pasaka took place in Egypt, where our ancestors applied the blood of the lambs to the sides and tops of their doorposts as a sign of protection. The lambs were roasted over fire, accompanied by bitter herbs and bread made without yeast. This meal was eaten in haste, with sandals strapped on their feet and staffs in hand, signifying readiness for immediate departure.

That same night, the Most High struck down the firstborn of Egypt but spared the Bantu who bore the blood-marked sign upon their homes. As commanded in Exodus 12:26–27, when future generations inquired about the meaning of Pasaka, parents were to declare that it commemorated the Most High’s passing over the houses of His people on the night He smote the Egyptians.

Throughout Bantu history, Pasaka remained a festival of supreme importance. The Chronicles record in detail two monumental celebrations: one during the reign of Hezekiah (2 Chronicles 30) and another during the reign of Josiah (2 Chronicles 35:1–19).

2. The Feast of Unleavened Bread (Mkate Bila Chachu):

The Feast of Unleavened Bread, known in Bantu as Mkate bila chachu, commenced immediately after Pasaka and lasted for one full week. During this time, the Bantu abstained from eating bread made with yeast and carefully removed all traces of leaven from their homes.

The festival was marked by sacred assemblies held on both the first and the seventh days, during which no work was to be performed except for the preparation of food.

In the context of the Exodus, unleavened bread symbolized the urgency of departure—bread without yeast could be prepared quickly, reflecting the haste with which our ancestors left Egypt. Yet, over time, the deliberate avoidance of yeast during this festival took on a deeper meaning. Yeast came to symbolize the pervasive influence of sin and corruption, something to be purged entirely from the community.

For this reason, yeast was not permitted in most grain offerings presented to Tata Nzambi (see Leviticus 2:11), reinforcing the principle of purity and holiness in worship.

3. The Feast of Firstfruits (Matunda Kwanza):

The Feast of Firstfruits, known in Bantu as Matunda kwanza, marked the beginning of the harvest and expressed the people’s gratitude and dependence upon Sonini Nanini (Leviticus 23:9–14). The very term matunda kwanza later inspired the modern African cultural festival of Kwanzaa, which, like the biblical Firstfruits, celebrates the first yield of the harvest.

Traditionally, the Bantu Feast of Firstfruits is celebrated across Africa around September, yet in the biblical record it is described in conjunction with the Feast of Unleavened Bread, focusing on the barley harvest. There was also another offering of Firstfruits observed at the Feast of Weeks (Wavuno) (Numbers 28:26–31) to commemorate the grain harvest. This shows that the Bantu people brought offerings of their harvest to the Most High at different times throughout the agricultural year. Still, there was always a special annual celebration of Matunda kwanza in connection with Pasaka—precisely seven weeks before Wavuno (Leviticus 23:15).

According to Leviticus 23:9–14, each Israelite was commanded to bring a sheaf of the first grain of the harvest to the priest. The priest would then wave this sheaf before the Most High on the day after Samba (Sabato) as a holy offering. Along with it, the worshiper presented a yearling lamb and a grain offering. Importantly, no one was permitted to eat from the new harvest until this sacred offering had been made.

Although Leviticus 23 does not explicitly link the Firstfruits to the Exodus, Deuteronomy 26:1–11 commands that when the Bantu presented their firstfruits, they were to openly declare that the Most High had delivered them from Egypt and had given them the promised land. Thus, the offering of the Firstfruits was not only an act of thanksgiving but also a confession of faith—an acknowledgment that the harvest was the gift of Tata Nzambi’s grace. In giving the very first portion of their produce, Israel learned a deeper lesson: not to hoard, but to trust the Creator for continual provision.

4. The Feast of Weeks (Mavuno / Pentecost):

The Feast of Weeks, known in Bantu as Mavuno, was celebrated seven full weeks after the wave offering of the Firstfruits during Samba (Leviticus 23:15–20; Deuteronomy 16:9). This placed it in the third month of the Bantu year and marked the joyful conclusion of the grain harvest.

Exodus 23:14–19 refers to this celebration when it names the Feast of the Harvest and links it with the Feast of Unleavened Bread and the Feast of Ingathering (Booths) as the three great agricultural festivals of the Bantu (see also Deuteronomy 16:16; 2 Chronicles 8:13).

While Deuteronomy 16:10 emphasizes that each individual was to make an offering proportional to the size of their harvest, the priestly instructions in Leviticus 23:17–20 and Numbers 28:27–30 provide detailed regulations regarding the sacrifices presented on behalf of the entire nation.

At its heart, the Feast of Mavuno was a festival of thanksgiving—an acknowledgment that every grain gathered from the fields was a blessing from Tata Nzambi. It reminded the people to honor Him with the first and best of their produce and to recognize their complete dependence on His provision.

5. The Feast of Trumpets: From the Bantu Baragumu, this feast is observed on the first day of the seventh Bantu month and is to be marked as a sacred holiday with a solemn assembly and special sacrifices (Lev 23:23–25; Num 29:1–6). Numbers 29:1 designates it as “a day of trumpet blast”, hence its traditional name, Baragumu. Numbers 10:1–10 establishes that trumpets were sounded at the new moon; thus, the interpretation of this festival as a trumpet-blasting day is both reasonable and consistent with ancient practice.

Since every new moon was regarded as a sacred occasion in the Bantu calendar, the question arises as to why the new moon of the seventh month is endowed with such unique significance. The Book of Enoch and Jubilees 6:23–27 provide insight: “On the new moon of the first month, on the new moon of the fourth month, on the new moon of the seventh month, and on the new moon of the tenth month are days of remembrance, marking the seasons in the four divisions of the year. These are written and ordained as an eternal testimony. Noah established them for himself and his descendants as perpetual feasts, serving as a memorial unto him. On the new moon of the first month, he was commanded to build the ark; on that very day, the earth became dry, and he opened the ark and beheld the ground. On the new moon of the fourth month, the mouths of the depths of the abyss were sealed. On the new moon of the seventh month, all the openings of the abysses of the earth were released, and the waters began their descent. On the new moon of the tenth month, the peaks of the mountains appeared, and Noah rejoiced.”

There exists a distinction between an agricultural year, a fiscal year, or an academic year—each differing from the official Bantu calendar year. From an agricultural perspective, the seventh month marked the conclusion of the year, yet the beginning of the new year did not arrive until the following spring. Our Bantu forebears did not adhere to a single, uniform calendar throughout their history; rather, they adopted varying systems depending on the lands to which they migrated or in which they were held captive. One such example is the solar calendar, still used by some today, modeled after the Khoisan’s Adam’s Calendar.

For those following Jewish traditions, it is crucial to recognize that the Feast of Baragumu marked the closure of the agricultural year, not the official beginning of the year. The seventh month held special weight not only for this reason, but also because it encompassed two major sacred observances: the Day of Atonement (Toba) and the Feast of Booths (Sukah). The sounding of the trumpets on the first day was, therefore, a jubilant proclamation of the arrival of this profoundly significant month (Leviticus 23:23–25).

6. The Day of Atonement (Toba):

The Day of Atonement, known in Bantu as Toba, was the most solemn and sacred day in the Bantu calendar, devoted entirely to atoning for the sins of the people. Its significance is detailed extensively in Leviticus 16, and the gravity of the observance is emphasized by the instruction given to Moshe “after the death of the two sons of Aaron who died” (Leviticus 16:1), highlighting that this was not a ceremony to be undertaken lightly.

The observance of Toba is also referenced in Leviticus 23:26–32 and Numbers 29:7–11, where it is described with brevity yet with unmistakable importance. The ritual took place on the tenth day of the seventh month of the Bantu calendar and is rich in symbolism, serving as the appointed day of repentance, reflection, and purification. On this day, the people were called to humble themselves before Tata Nzambi, confess their sins, and seek reconciliation, reinforcing the profound spiritual discipline at the heart of Bantu worship.

7. The Feast of Booths (Sukah / Tabernacles or Ingathering):

The Feast of Booths, known in Bantu as Sukah, was observed on the 15th day of the seventh Bantu month, precisely five days after the Day of Toba. The festival is described in Leviticus 23:33–43 and Deuteronomy 16:13–15, with the most detailed instructions recorded in Numbers 29:12–40.

For seven days, the Bantu presented offerings to Tata Nzambi, living in temporary huts constructed from palm fronds and leafy branches. The purpose of residing in these booths was to commemorate the sojourn of the Bantu people prior to entering the land of Canaan (Leviticus 23:43).

This week-long festival was intended to be a time of joy, celebration, and thanksgiving for the harvest of the year (Deuteronomy 16:14–15). By leaving the comfort of their permanent homes and living in these temporary dwellings, the people were reminded that all the blessings of the promised land are gifts from Tata Nzambi—they cannot be hoarded or taken for granted.

At the same time, this return to a period of living as strangers fostered a sense of national community, recalling the collective experience of the Exodus and reinforcing gratitude, humility, and spiritual unity among the people.

8. The Feast of Dedication (Ushindi):

The Feast of Dedication, known in Bantu as Ushindi, commemorates the recapture and purification of the temple from the Greek forces of Antiochus IV around 164 B.C. This sacred observance occurs on the 25th day of the ninth month of the Bantu calendar.

The initiation of the festival is described in 1 Maccabees 4:52–59, highlighting the dedication of the temple and the restoration of worship according to the Most High’s commandments. The festival is further referenced in John 10:22–23, where it is noted as the time when Yisayah walked in Yahsalama during the celebration.

Ushindi serves as a powerful reminder of faith, resilience, and victory—a testament to the Bantu people’s unwavering devotion to Tata Nzambi, even in the face of oppression. It is a celebration of triumph, spiritual renewal, and the restoration of sacred order in alignment with the Most High’s divine law.

9. The Sabbath Day (Samba / Sambuadi):

The Sabbath, known in Bantu as Samba or Sambuadi, was observed every seventh day to honor both the creation of the world (Exodus 20:11) and the deliverance from Egypt (Deuteronomy 5:15). It was a sacred day of rest, praise, and dance, deeply embedded in Bantu spiritual life, and was not to be neglected or violated (Numbers 15:32–36).

The Book of Jubilees (50) provides explicit instructions regarding what is to be done and what is to be avoided on the Sabbath, underscoring its sanctity and the discipline required to observe it properly. Samba was more than a day of cessation from labor—it was a time to reconnect with Tata Nzambi, celebrate creation, and renew communal and spiritual bonds through worship and joyful expression.

10. The Feast of the New Moon (Mwezi):

The Feast of the New Moon, called Mwezi in Bantu, marked the first day of every lunar month. It was observed with the blowing of trumpets and the offering of special sacrifices (Numbers 10:10; 28:11–15). As a regular, periodic worship day, the New Moon is often mentioned alongside the Sabbath, reflecting its equal importance in maintaining the rhythm of sacred time (2 Kings 4:23; Amos 8:5).

According to the Book of Jubilees (6), certain New Moons carried even greater significance. Specifically, the 1st, 4th, 7th, and 10th New Moons of the year were to be kept as special feast days. These marked pivotal divisions in the Bantu sacred calendar, anchoring the community to the cycles of creation, agricultural seasons, and divine covenant. Observing Mwezi thus reaffirmed order, renewal, and alignment with Tata Nzambi’s appointed times.

BOOK REFERENCE:

“SUNSET TO SUNSET OUR BANTU CALENDAR” BY YAHUNDE BATAKANE

BIBLE REFERENCES:

Genesis 1:5-19, 2:1-3; 13-14; Sirach 43:6-8; Psalms 104:19; 81:3; Numbers 9; 10:1-10; 28:11-15; 15:32-36; Exodus 12:1-20; 20:8-11; 40:2; Ezra 7:9; Deuteronomy 5:15; Leviticus 23:1-37; 1 Maccabees 4:52-59; 2 Maccabees 15:36, John 10:22-23; 1 Chronicles 23:30-31; 2 Chronicles 2:4; 8:12-13; 31:3; Nehemiah 10:32-33; 13:19; Ezekiel 45:17; 46:1; 1 Samuel 20:5; 2 Kings 4:23; Amos 8:5; Isaiah 58:13-14; 56:1-8; 66:23, Jubilees 2:9; 6:23; 6:30-38; 49:14-23; Enoch 73:13-16; 74:1-17; 75:1-9; Revelation 11:1-3; Acts 17:2; Luke 4:16, Matthew 14:25.

FURTHER REFERENCES:

Seasons of Sowing seeds:

https://cropcalendar.apps.fao.org/

Atlas global weather:

https://www.weather-atlas.com/en/democratic-republic-of-congo/kinshasa-climate

New year in Egypt:

https://www.egypttoday.com/Article/4/22184/September-11-marks-the-beginning-of-a-new-Egyptian-year

New year in Ethiopia:

https://allaboutethio.com/tcalendar.html

Moon phase of South Africa:

https://www.timeanddate.com/moon/south-africa/johannesburg

Moon phase of Congo:

https://www.timeanddate.com/moon/phases/congo-demrep/goma

Moon phase of Kenya:

https://www.timeanddate.com/moon/phases/kenya/nairobi

Moon phase of Egypt:

https://www.timeanddate.com/moon/phases/egypt/cairo

Moon phase of Ethiopia:

https://www.timeanddate.com/moon/phases/ethiopia/addis-ababa

General moon phases:

https://www.calendar-12.com/moon_calendar/2020/september

Understanding the moon phases:

https://earthsky.org/moon-phases/understandingmoonphases

Understanding the Moon connection:

https://www.moonconnection.com/moon_phases.phtml

Understanding the Biblical festivals:

https://www.biblestudytools.com/…/feasts-and-festivals…

Understanding the Bantu as the Israelites

https://www.facebook.com/106425311634238/posts/118510763759026/?d=n

Understanding the location of the promised land

https://www.facebook.com/106425311634238/posts/118502280426541/?d=n

Find screenshots of the calendar here

https://bantubiblicalisraelites.wordpress.com/2021/02/17/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-bantu-biblical-lunar-calendar/

Find screenshots of the calendar here

https://bantubiblicalisraelites.wordpress.com/2021/02/17/everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-bantu-biblical-lunar-calendar/